Sinclair Vehicles – how one of UWSP’s first tenants was ahead of its time despite failure

With the University of Warwick Science Park celebrating its 40th anniversary this year, we’re taking a look back at some of its history and speaking to former tenants or those connected to the Science Park to share their stories.

One of the Science Park’s earliest tenants was the late Sir Clive Sinclair, the computer mogul behind pocket calculators and the ZX Spectrum. However, it was his ill-fated yet iconic electric tricycle, the Sinclair C5, that would be developed at the Science Park.

We caught up with Sir Clive’s son Crispin about his father’s work and how his eye for solving problems is benefiting Crispin’s own business, Conker of Cambridge, as well as Barrie Wills, the former MD for Sinclair Vehicles, about his memories.

In the early 1980s, Sir Clive Sinclair was a household name in the home computing, video gaming, and electronics industries, with his ZX series of computers and the Sinclair Executive pocket calculator behind much of this success.

But in 1983, Sir Clive shifted his focus from computing and towards transportation by founding Sinclair Vehicles – a company dedicated to the production of electric vehicles under the Sinclair name.

A year later, shortly after the University of Warwick Science Park was opened off Sir William Lyons Road by the then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, Sinclair Vehicles decided to make the move to Coventry and base itself at the Science Park, right in the heart of the motor industry.

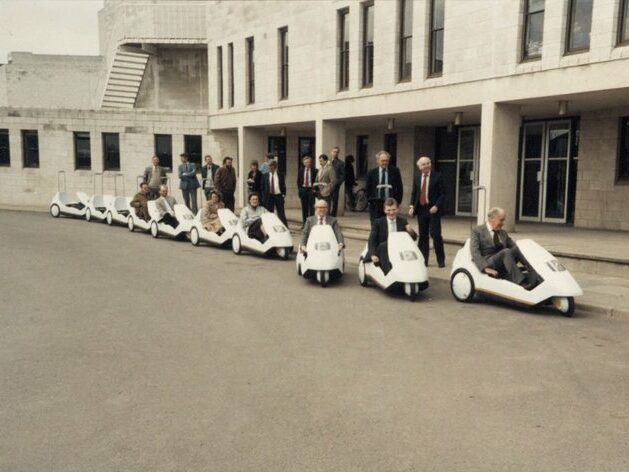

It was at the Science Park where the project management of Sir Clive’s most infamous product, the Sinclair C5, was undertaken.

A personal electric ‘tricycle’ that combined electric power from batteries with pedal power, the C5 was one of the first ever electric vehicles aimed at the mass market.

With backing from a number of bodies, including The Ministry of Transport; The Department of Industry; The Electricity Council; the AA; the RAC; the Police; the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA); and the Motor Industry Research Association (MIRA), there was nothing to suggest the C5 would be anything other than a success.

However, problems with battery life and performance, a lack of market research, and a borderline disastrous press launch featuring failing batteries and inclement weather, meant the C5 got off to a very shaky start.

Unfortunately, the C5 could not recover from this, and in August 1985, production was wound up.

Barrie Wills, the managing director of Sinclair Vehicles at the time, had every reason to believe the new vehicle would be a success.

“Everyone that saw and drove the C5 during and after its engineering and development by Lotus Engineering was impressed,” he said.

“However, the press launch was held at the wrong time of year and in the wrong place: Alexandra Palace at the top of a hill in winter. We pleaded with Clive not to hold it in January but he insisted. It snowed!

“Despite that, press coverage over the first 24 hours following the launch was very favourable. For one, Sir Stirling Moss, an automotive journalist at that time, was full of praise for it.

“Had it been launched today in a slightly different form, benefitting from a change of legislation that has removed the strict 60kg weight limit, it could have been a success as the public is now familiar with electric vehicles, and cycle lanes on roads are commonplace.

“We had great support from the director of the Science Park at the time, David Rowe. David and his small team could not have been more accommodating towards us. He recognised the prestige of having a Sinclair company located there which would, he thought, attract other businesses. The benefits were, therefore, very much two-way.

“While the C5 was not the success we hoped for, it was clear to us the Science Park would succeed with David at the helm. It is more than impressive that 40 years on it is still going strong.”

Sir Clive’s son, Crispin, who has invented his own product to help children become safer on bikes while a parent cycles them to school, remembers how the C5’s demise did not dishearten his father.

“My dad always had a knack for problem-solving,” he said.

“He would see all sorts of things throughout his day-to-day life and think he could improve it in some way with a bit of tinkering.

“As a child, I would often witness this and also hear about his ideas at the dinner table before any of the public did.

“By the time the C5 came around, I was focusing on my A-Levels and I didn’t venture up to Coventry very often – although I recall meeting the Lotus team when it was working on the C5’s chassis.

“Even though it did not succeed commercially, I don’t remember my dad being particularly downbeat about it, or if he was, he didn’t show it.

“I think my dad was prepared to take risks when inventing products. He would rather try and bring an idea to life than shelve it in case of failure.

“I’d like to think I’ve picked up a little bit of that spirit from him, and I certainly think his ability to look at a product and find a way to improve it has rubbed off on me.”

To that end, Conker of Cambridge, Crispin’s company, is aiming to improve the safety of children who are being cycled to school or elsewhere by a parent or guardian.

Crispin has invented a welded aluminium ‘box’ that fits over the top of a cargo bike where a child would sit, protecting them from impact in the event of a collision.

It is also developing future products that can fit on the back of regular bikes.

“Protection for riders and passengers on bikes is incredibly flimsy at the moment,” Crispin added.

“While there are plenty of accessories that make riders more visible, the only thing protecting you in the event of a collision is a helmet, which does not do a great deal.

“What our product does is provide a lightweight yet strong barrier between the child passenger and another vehicle, reducing the severity of impact while also preventing the bike from being dragged under its wheels.

“Research has consistently shown the biggest barrier to take-up of cycling is safety. What our product aims to do is provide confidence to parents that their children will be safe if they decide to cycle them to school instead of driving.”

While Crispin is hopeful Conker won’t go the way of the C5 commercially, he thinks his dad’s invention had its part to play in the evolution of transport.

He said: “While the market wasn’t there in the 1980s, I think my dad had shown that electric vehicles and personal transport solutions outside of bicycles were possible.

“The C5 was undoubtedly inconvenient, but improved technology and a political will to encourage EV take-up means it may have done better in today’s market with some quality-of-life improvements.

“You only have to look at the Science Park to see how much the market has changed. It is now full of companies looking to make electric vehicles more efficient or perform better, and it works with plenty of start-ups with their own ideas around personal transport.

“Indeed, Conker is part of that – we want to help parents make the choice to cycle when many would prefer to drive.

“It’s great to see how far the industry has come since my dad created the C5, and that the Science Park is still supporting so many companies 40 years on to take advantage of the far bigger market out there for them.”